In late 2017 we decided to try and make an elephant collar that was robust enough to withstand the brutality of an elephant moving around in the African bush, but still have enough flexibility in its design to be able to refurbish it in the field. Refurbishing a collar would mean changing the batteries and perhaps the belting if it had worn through. Field-refurbishment of collars saves money because the end-user doesn’t have to buy a replacement collar to fit onto the animal (even at a reduced price). Cost is also reduced because the User doesn’t have to send the collar back to the manufacturer.

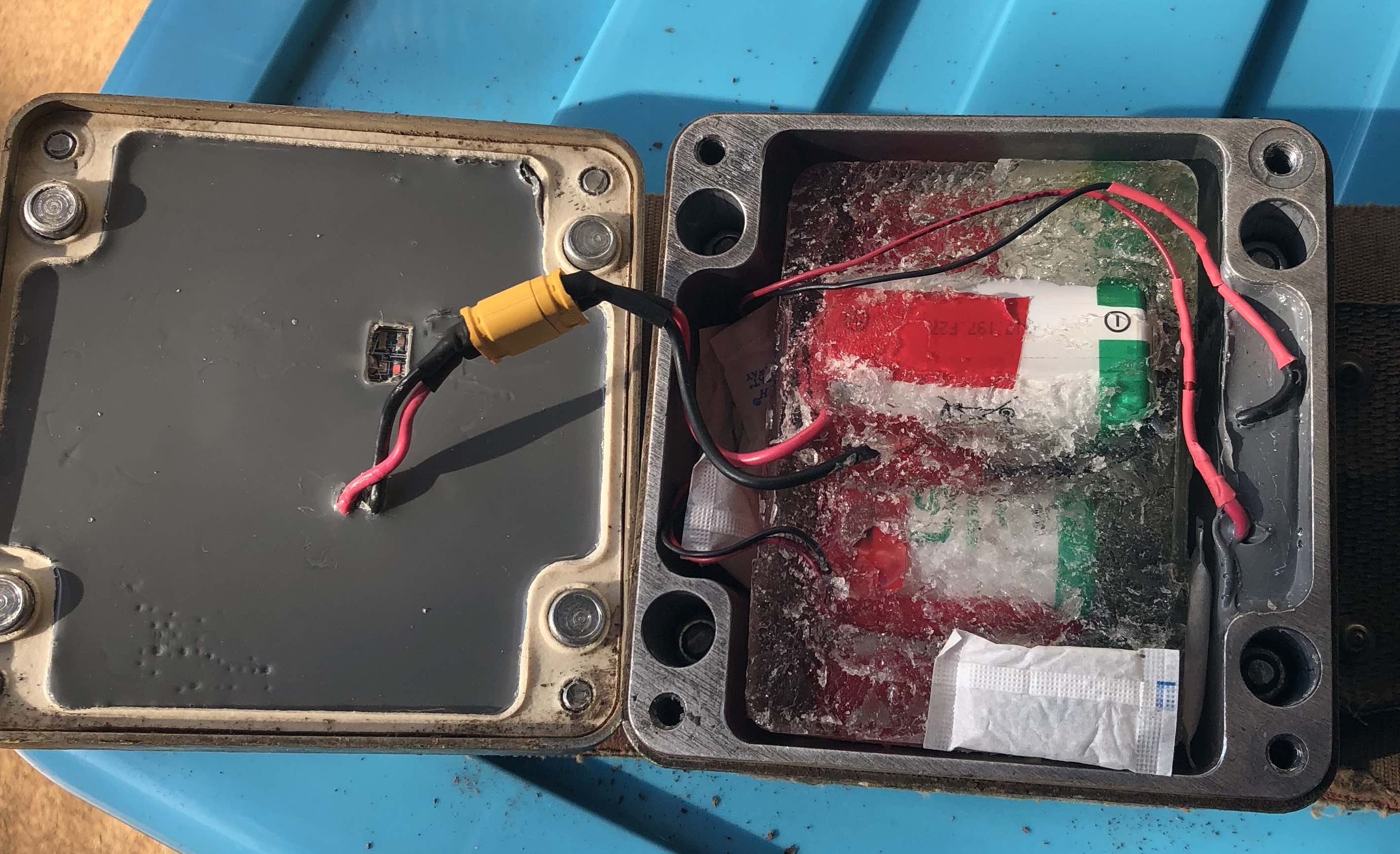

One of the other major driving forces behind making an elephant collar that one could replace batteries in the field were the regulations from Aviation Authorities with regards to the shipping of products with Lithium Batteries. We wanted to be able to ship the collar separately from the batteries as well as be able to have the Collar User make up their own battery packs where possible. It would be a simple matter of releasing four screws on the lid of the enclosure, disconnecting the old battery pack and connecting the new one.

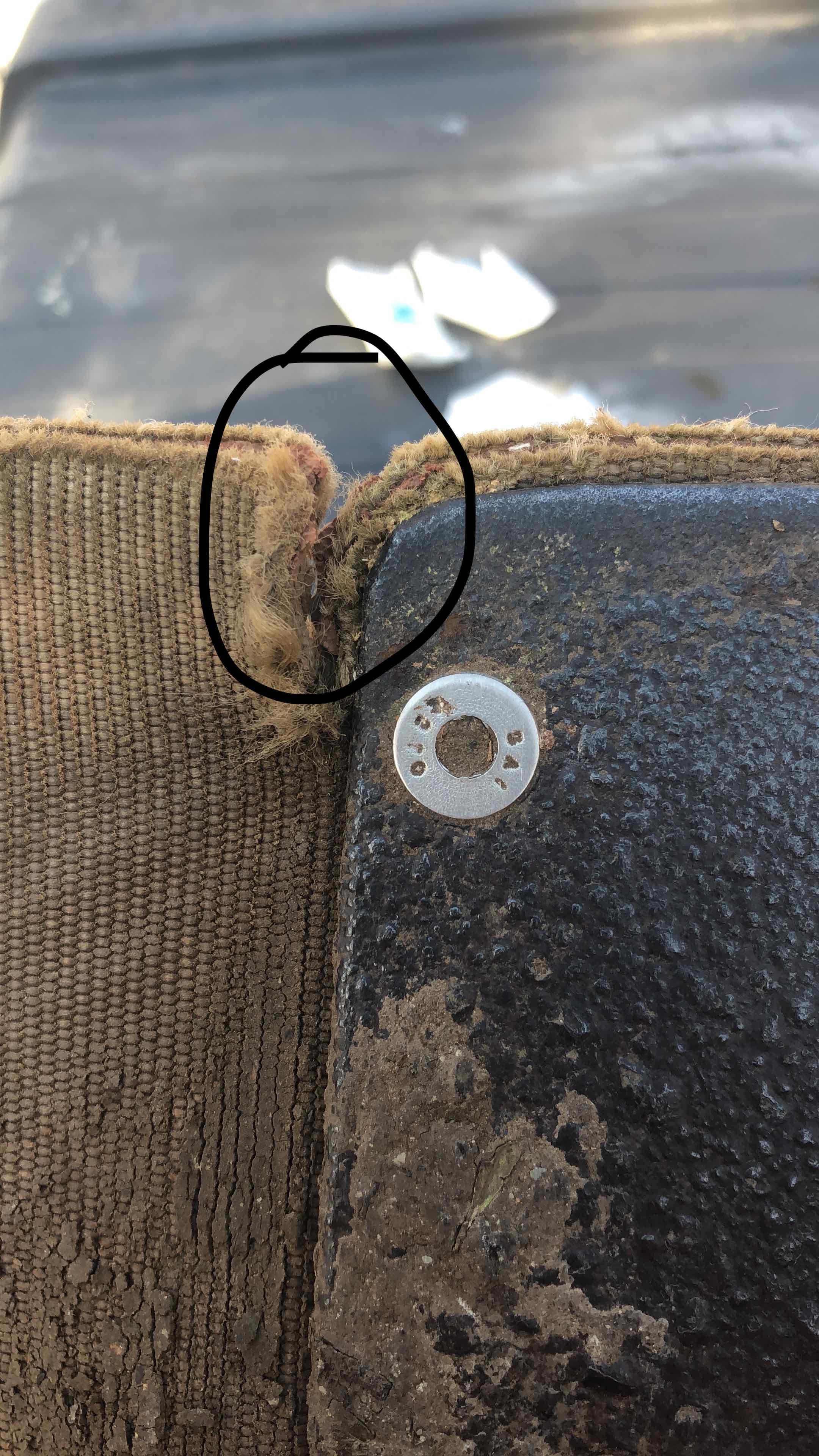

The size of the enclosure was an immediate concern. Having a metal enclosure strong enough to bolt onto a belt meant that its profile was relatively high to accommodate the battery pack. We used six D-type lithium primary batteries in each collar. In retrospect we should perhaps have started with three cells. This and the heavy counterweight required to keep the top enclosure facing the sky meant that the strain on the belting was too much. The continuous rocking motion of the elephant walking as well as the occasional snagging of the enclosure on vegetation meant that the belting tore, almost in a straight line, where it was attached to the enclosure.

A failed collar is an expensive exercise, not only from a time and materials point of view but also the additional expense of having to re-collar the animal. Chopper time, vet bills and ground crew are not cheap, not to mention the additional stress placed on the animal during recapture. There is also the reputational damage that a failed collar incurs. We would like all prospective customers to know that we have gone back to making the collars the “old-fashioned” way. Smaller profile and lighter weight. We will have to think of another way to make an elephant collar field-refurbishable! Field testing an elephant collar is not an easy thing to do. The time it takes to judge the success of a design is significant and waiting three years to see if an experimental collar is working in the field before making the production version available is not feasible. We hope that this post will help future collar manufacturers learn from our design flaws and improve on them.

For more information on this story, or to find out about collar-making, please give me a shout at jason@awetelemetry.co.za. I am happy to share my experiences so that we can all make better collars in the future.